The stock market and consumer confidence are vital indicators often used to assess the economy’s health. While they frequently move in tandem, there have been notable periods in history when the stock market surged despite faltering consumer sentiment and vice versa. For investors, understanding the dynamics of a confidence dichotomy is crucial.

Consumer confidence reflects the optimism or pessimism consumers feel about their financial situation and the state of the economy. The Conference Board’s Consumer Confidence Index (CCI) is one of this sentiment’s most widely used measures; the other is the University of Michigan Sentiment Index. Logically, when consumer confidence is high, individuals are more likely to spend, borrow, and invest, driving economic growth. Conversely, when confidence is low, consumers tend to save more and spend less, which can slow down the economy.

As former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke pointed out in 2010, the link between consumer confidence and the stock market is critical to the Federal Reserve’s risk assessment.

“This approach eased financial conditions in the past and, so far, looks to be effective again. Stock prices rose and long-term interest rates fell when investors began to anticipate the most recent action. Easier financial conditions will promote economic growth. For example, lower mortgage rates will make housing more affordable and allow more homeowners to refinance. Lower corporate bond rates will encourage investment. And higher stock prices will boost consumer wealth and help increase confidence, which can also spur spending.”

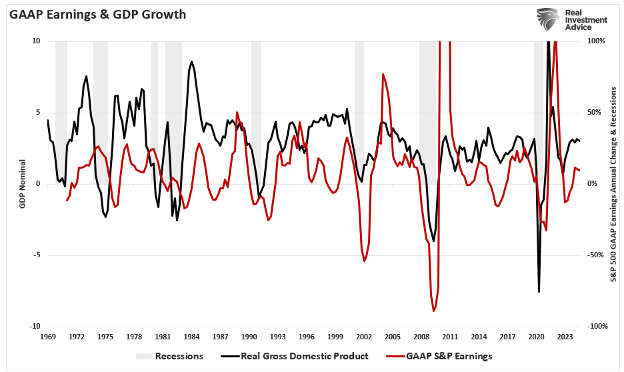

The last sentence is crucial. The Federal Reserve depends on a rising stock market to boost consumer confidence. Creating a “wealth effect” makes people feel more financially secure, which increases economic activity. Notably, as we have discussed previously, and should be obvious, corporate earnings are derived from economic activity.

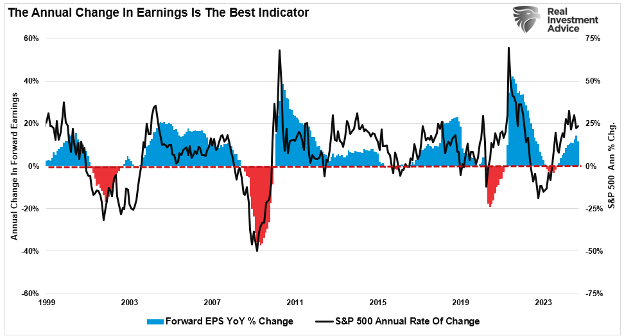

Naturally, if earnings are increasing, investors are willing to pay more today in exchange for increased earnings in the future, leading to higher asset prices. As shown many times, the annual earnings change is the best indicator of future stock market returns.

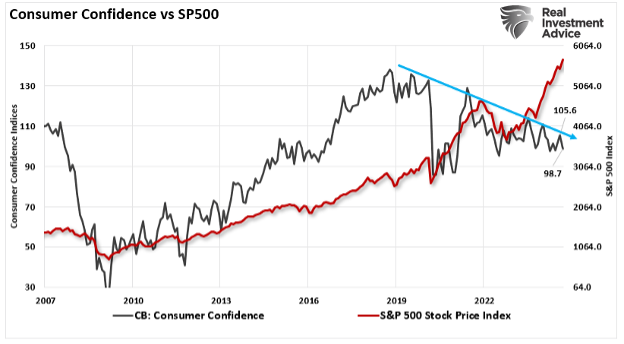

However, the “confidence game” to which the Federal Reserve pays attention isn’t always linear. Sometimes, the stock market rallies even when consumers are skeptical about the future, leading to a disconnect between Wall Street’s exuberance and Main Street’s reality. That particular confidence dichotomy exists currently, but it isn’t the first time.

The latest Conference Board Consumer Confidence Index dropped sharply in the latest reading. While expectations were for a small decline from 105.6 to 104, the actual reading came in at 98.7. Yet, at the same time, the market has surged unabated.

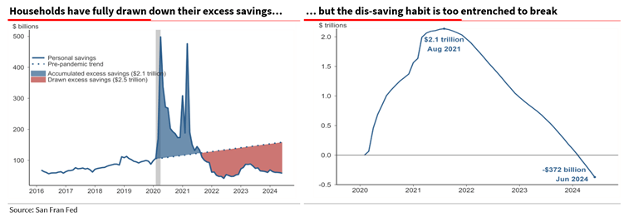

You will notice that confidence collapsed, as expected, in March 2020 and then sharply recovered as the Government sent $1500 checks to households. However, since then, the confidence trend has continued to trend lower as excess savings continue to erode. As noted by Albert Edwards this week, it could be claimed that the savings rate decline resulted from consumers dipping into their pandemic-era excess savings to support economic spending. However, that argument no longer holds

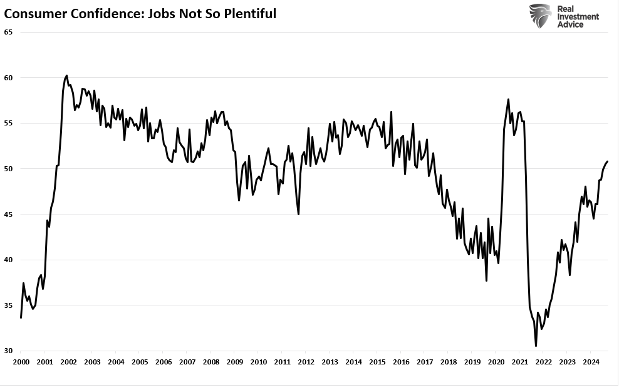

Given the drain in savings, combined with rising concerns over job loss, it is unsurprising that consumer confidence has continued to weaken.

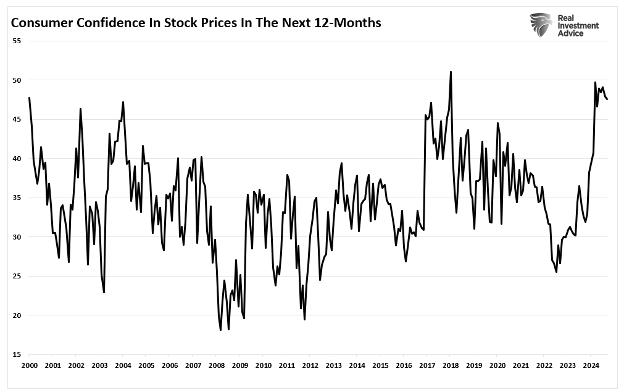

However, consumer confidence in higher stock prices in the next year remains at the highest since 2018, following the 2017 “Trump” tax cuts.

Of course, the differential is that those with money invested in the financial markets are “feeling great” about their portfolio, just not so much with anything else.

However, the question is, is this “consumer dichotomy” an anomaly, or can we refer to previous periods? The answer is “yes.”

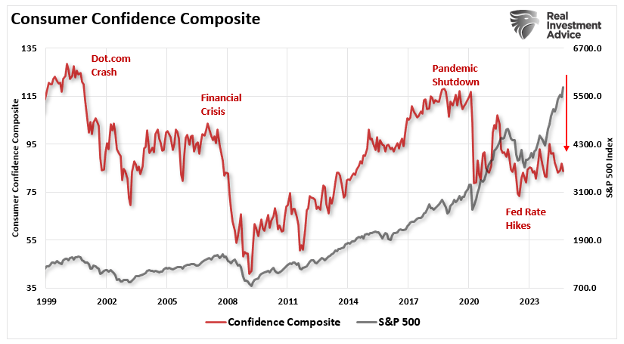

The chart below is a composite consumer confidence index, the combined score of the University of Michigan and Conference Board measures. The composite gives us a broader measure of consumer confidence from a historical perspective. As shown, there have been three previous periods where the market rallied despite falling consumer confidence.

- The Dot-Com Bubble (1999–2000)

One of the most famous examples of stock market exuberance detaching from consumer sentiment occurred during the dot-com bubble in the late 1990s. However, consumer confidence did not keep pace as the underlying economy weakened. By the early 2000s, cracks appeared in the economy and began to show in corporate earnings statements. The fallout from the dot-com bubble wiped out trillions of dollars in market capitalization, leading to a significant drop in consumer confidence and a mild recession.

- The Global Financial Crisis (2007–2009)

The stock market experienced an impressive run in the years before 2008. However, consumer confidence began to falter as early as 2007. Concerns over the housing market festered as mortgage defaults rose in the subprime mortgage market. Despite the early warning signs, the stock market continued its climb until the realization that slowing economic growth and recession caused a market valuation correction. Consumer confidence plummeted alongside the market, and the U.S. economy entered the Great Recession, leading to a significant bear market and widespread financial pain.

- COVID-19 Pandemic (2020)

The most recent example occurred in early 2020. As the virus spread across the globe, consumer confidence plummeted due to rising unemployment, widespread lockdowns, and uncertainty about the future. The composite sentiment index shows that while consumer confidence hit multi-year lows in April 2020, it struggled ahead of the pandemic’s onset.

What can we learn from this? While the stock market can initially remain optimistic, the dichotomy between the consumer and the financial markets is unsustainable. Eventually, confidence must align with the market or vice versa. Historically, as shown, it has been the latter as the markets are disappointed by the realization of slowing earnings growth.

Lastly, the one common ingredient of every realignment of the markets and weak consumer confidence was a recession and bear market.

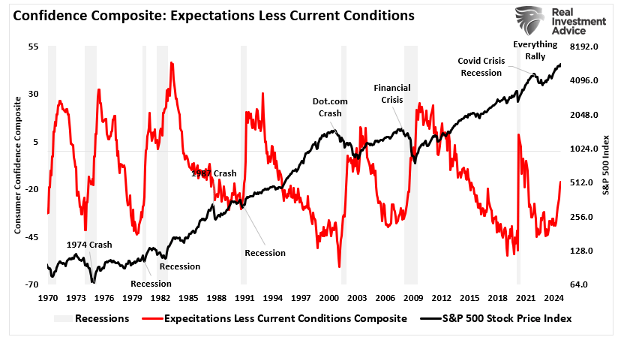

When stock market exuberance becomes detached from consumer confidence, it previously signaled increased risk for investors. One last measure to review is the spread between what consumers “expect” in the future and their view of their present situation. Historically, whenever that spread spiked sharply higher, as recently, it was in concert with a recessionary onset. Yet, currently, investors are chasing every risk asset, from stocks to gold to options, with increasing levels of speculative fervor.

The divergence is fueled by speculative risk-taking, investor overconfidence, or external factors such as increases in monetary accommodation, which drive up asset prices even when economic fundamentals are weak.

As noted above, the Federal Reserve hopes that creating the “wealth effect” can bridge the gap between weak economic demand and an eventual recovery. Historically, as noted, these confidence dichotomies are eventually corrected, with stock markets falling back in line with economic reality. Investors who remain cautious and consider consumer confidence and market performance can better navigate these turbulent periods.