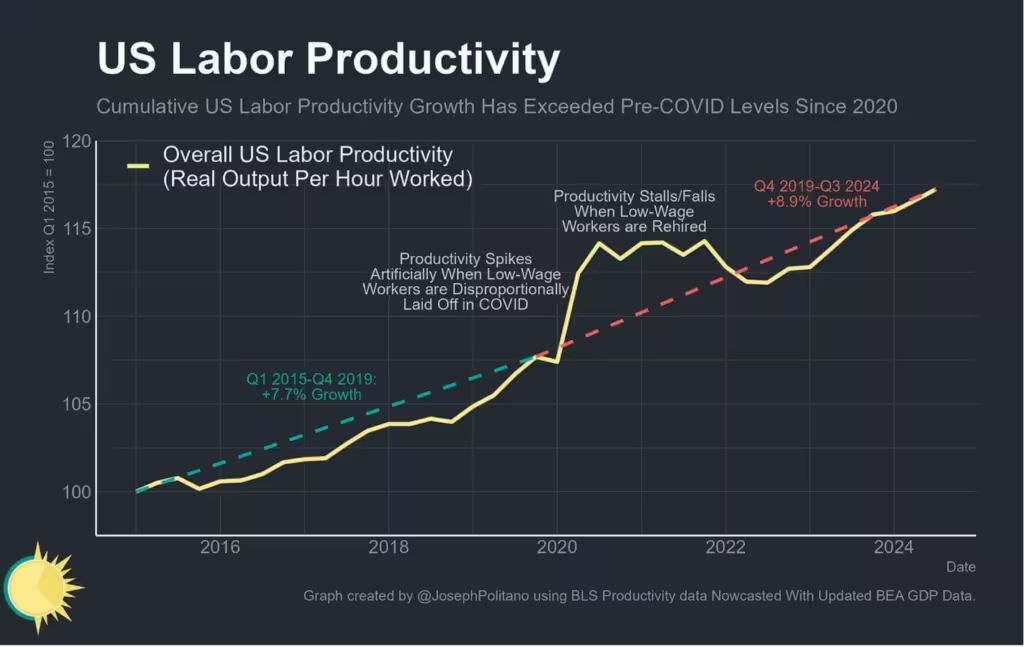

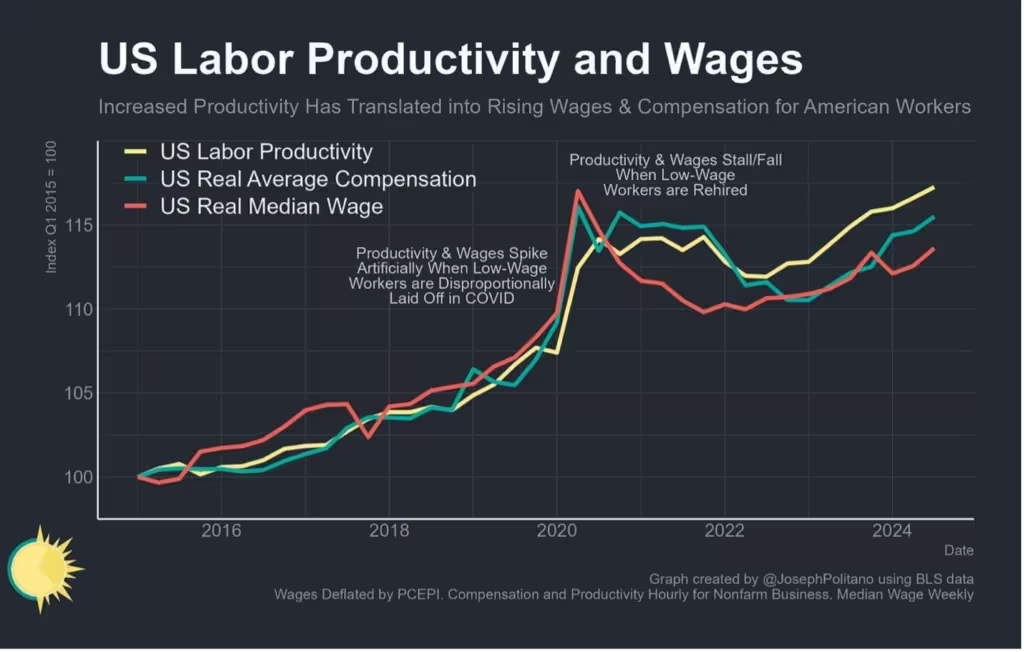

Productivity growth is nothing short of the bedrock of progress—in the long run, creating more with the same amount of labor is the only way to durably increase wages, consumption, and society’s overall prosperity. That makes it such a historic achievement that American economic output per hour worked has risen 8.9% over the last five years— faster than the five years prior or any point in the 2010s—in spite of the COVID-19 pandemic. The already-great productivity recovery we had going into this year got a major upward revision from recent updates to GDP data, and preliminary estimates suggest they’ll get another boost as job growth will likely be revised down significantly at the start of next year.

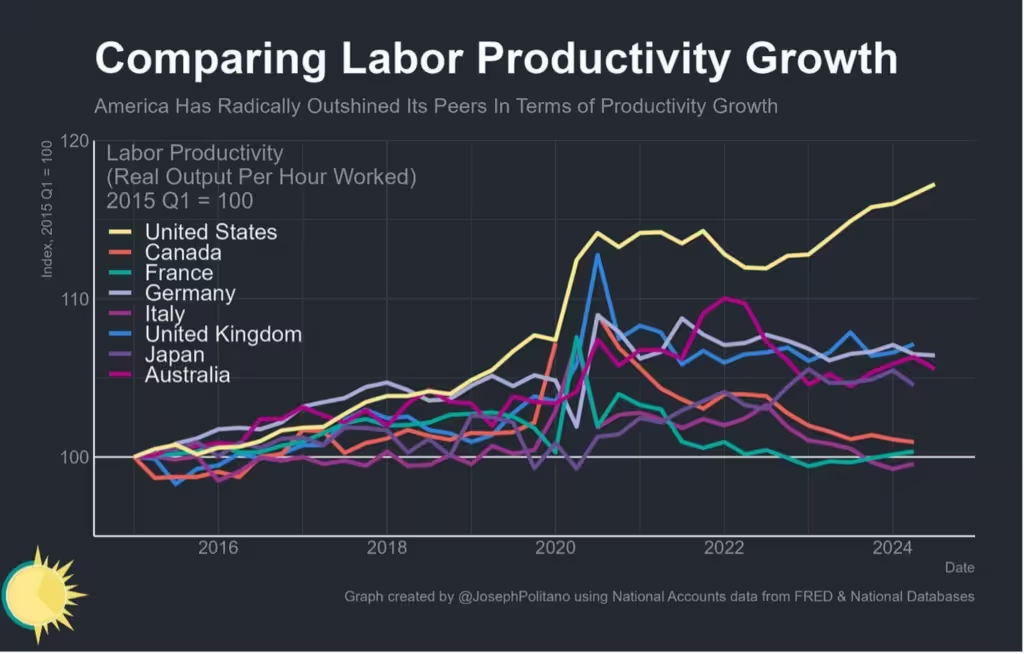

That success is all the more remarkable compared to the dismal productivity numbers seen across many of America’s peer nations and how long it took US productivity growth to sustainably recover from the Great Recession. Since late 2019, the US has seen more than double the productivity growth of the next-fastest major comparable economy, building on an already significant lead it built up in the years before COVID. Plus, unlike the 2nd-place UK, the US has achieved this while increasing overall employment levels instead of leaving less-productive workers out of a job.

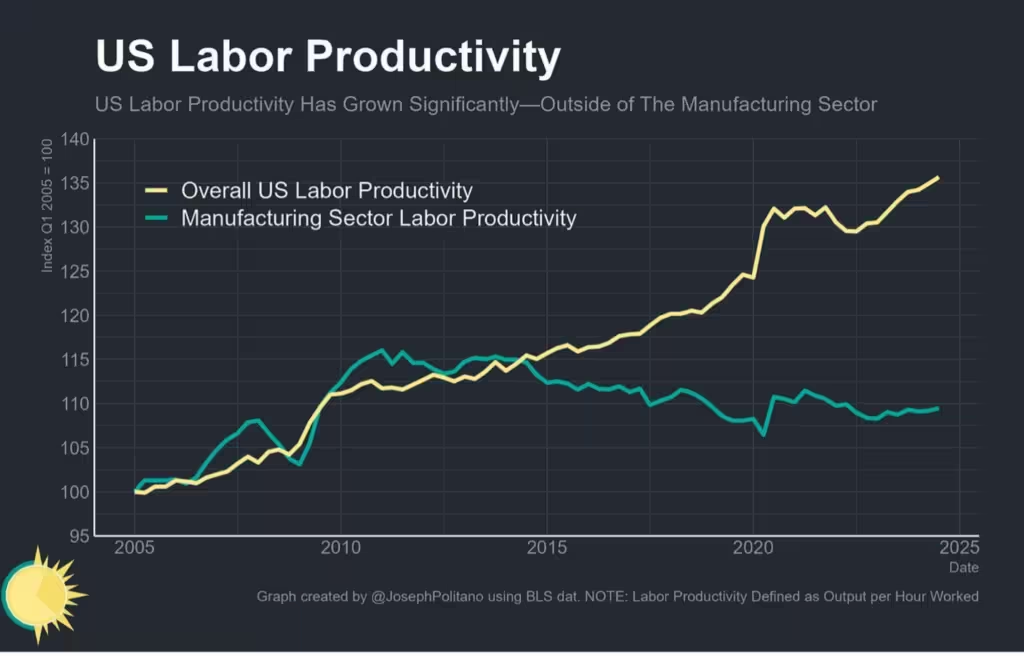

Historically, spurts of productivity growth are most concentrated in the manufacturing sector and manifest only slowly in services—in the classic example, it is hard for barbers to get faster at giving haircuts even as razor manufacturers rapidly get more productive. However, the endemic problems with American industry has meant that manufacturing productivity remains stagnant even amidst heavy government emphasis on industrial policy over the last four years. Thus, the nation’s recent productivity boom comes almost entirely from the service sector—cooks, programmers, drivers, nurses, bankers, teachers, cleaners, managers, caregivers, and more have all gotten significantly more efficient at their jobs over the last four years, with the gains in some subsectors being historically unprecedented in both speed and scale.

It is essential for America’s industrial policy efforts that manufacturing productivity growth return eventually, but it is much, much more beneficial for the country overall to have productivity improve among the service-sector jobs that make up the vast majority of employment, consumption, and economic output. The recent productivity boom has delivered significant gains in Americans’ real wages throughout the pay distribution, which in turn has enabled higher household consumption and increased personal welfare. The causes of this boom are multifaceted but primarily stem from the strength of America’s labor market in 2021 and 2022, when businesses invested significantly in productivityenhancing capital goods, work from home became a permanent facet of white-collar life, and Americans quit low-productivity jobs for high-productivity ones at record rates. That period of intense labor demand planted seeds that have sprouted into even greater efficiency as the labor market has cooled—newly hired employees have adapted to their higher-paying roles, businesses’ capital investments have steadily come online, and the supply chain issues present throughout the early pandemic have eased significantly. In many sectors and industries, the fundamentals of work were completely restructured in a way that forced greater efficiency.

Conclusions

To abuse an exercise metaphor, the US economy spent much of the immediate aftermath of the pandemic “bulking”—using expansionary fiscal and monetary policies to intentionally run the labor market hot. That helped America recover quickly from the pandemic and steadily build up its underlying “muscle strength”—productivity growth. Part of the consequences of that effort was the creation of “excess fat” as the rapid increase in aggregate demand overshot economic capacity and led to a surge in overall inflation. Then the US spent the last two years in the “cutting” phase—losing the “excess fat” by intentionally suppressing demand and cooling the labor market. That “cutting” has exposed how defined the muscles were under the surface, but if it goes too far the US could start losing muscle mass instead of fat.

Markets:

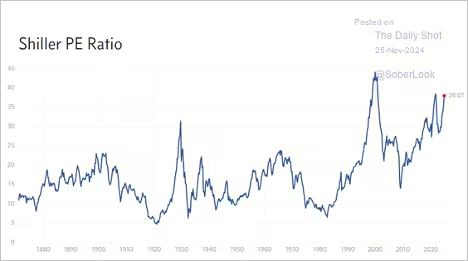

Goldman’s sentiment indicator keeps moving deeper into “stretched” territory. Retail investors’ call option bets have reached their highest level since 2021. US equities’ CAPE Ratio is nearing the highest level since the dot-com bubble.

Source: multpl

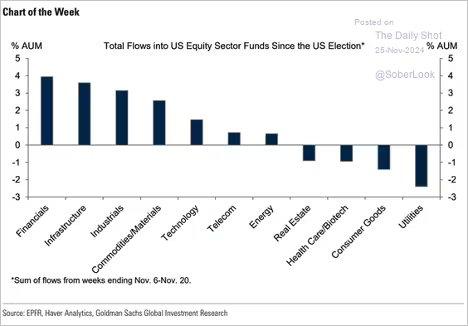

Nvidia is now over 7% of the S&P 500 market cap. Here is a look at the post-election fund flows by sector.

Source: Goldman Sachs; @WallStJesus

Market breadth has improved sharply in recent days. 80% of the S&P 500 members are trading above their 20-day moving average. Financials continue to rally, amid relatively strong earnings revisions. Gold and Silver have been hit hard recently. XLK is nearing the end of its ascending triangle.

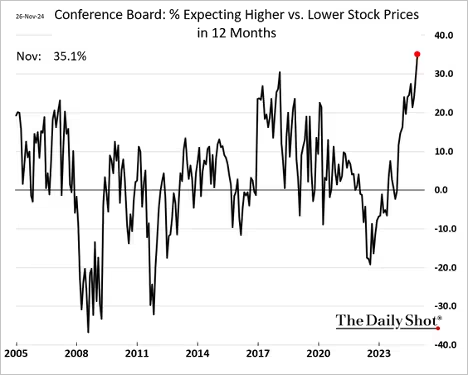

US households have not been this bullish on the stock market in recent decades.

Economy:

Trump’s pledge to impose 25% tariffs on Canada and Mexico pushed the dollar higher once again.

Source: Reuters Read full article

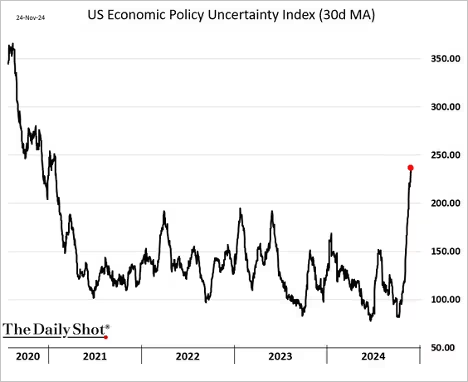

The US economic uncertainty index has been rising, …

… but Trump’s nomination of Scott Bessent as Treasury Secretary sparked a relief rally in both stocks and bonds. The Treasury curve (2s10s) inverted again. The US Manufacturing PMI from S&P Global remained in contraction territory this month. However, manufacturers have become optimistic about future output. The strength of the US dollar has been weighing on export orders. Factories are hiring again. Growth in US services activity accelerated this month. Businesses are less inclined to raise prices. The U. Michigan consumer sentiment index was revised lower in the second half of the month. Economists have significantly raised their estimates for US consumer spending growth in 2025.

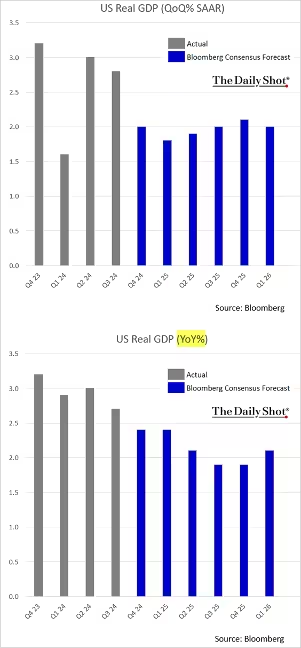

Here is a look at economists’ median forecasts for US GDP growth through the first quarter of 2026 (quarter-over-quarter and year-over-year).

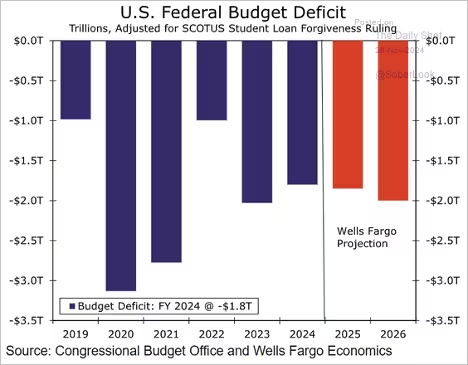

The federal budget deficit is forecast to widen over the next couple of years.

Source: Wells Fargo Securities

The Richmond Fed’s manufacturing index confirmed what we’ve been seeing in other regional Fed reports: soft current activity but improving outlook. An improvement in regional manufacturing activity points to a turnaround in the ISM manufacturing index.

The Fed

The FOMC minutes indicated that the Fed is in no hurry to cut rates, emphasizing a “gradual” approach to policy normalization.

“… it would likely be appropriate to move gradually toward a more neutral stance of policy over time. Some FOMC participants continue to express doubts about the accuracy of neutral rate estimates, creating uncertainty around the current monetary policy’s level of restrictiveness.

Many participants observed that uncertainties concerning the level of the neutral rate of interest complicated the assessment of the degree of restrictiveness of monetary policy and, in their view, made it appropriate to reduce policy restraint gradually. There was less discussion of inflation/prices. The number of credit-related comments increased. Inflation expectations dipped to pre-COVID levels.

Great Quotes

“If you are not aggressive, you are not going to make money, and if you are not defensive, you are not going to keep money.” – Ray Dalio

Picture of the Week

Moose, Denali National Park, Alaska

All content is the opinion of Brian Decker