The current forward price-to-earnings ratio on the S&P 500 based on 2020 earnings is 35.6 times earnings. The historical average forward price-to-earnings ratio on the S&P 500 dating back a century and a half is 15.6 times. Thus, today’s valuation is more than +125% greater than the historical average.

The forward P/E ratio on the S&P 500 has been higher than 35.6 only two other times in history. Both are recent episodes. The first was from 2001-Q1 to 2002-Q2 during the bursting of the technology bubble. The second was from 2008-Q2 to 2009-Q1 during the Great Financial Crisis.

During both of these past episodes, the P/E ratio moved in excess of 35 times forward earnings, because while the S&P 500 price was falling (the “P” in the P/E ratio), the earnings were falling much faster (the “E” in the P/E ratio). In contrast, the P/E ratio has moved in excess of 35 times forward earnings today because the S&P 500 price is rising even though earnings are falling considerably.

CLASSIC discussion of overpaying for a stock: Scott McNeely discussed the irrationality of paying 10x sales for a company in a 1999 Bloomberg interview, when he was CEO of Sun Microsystems: “At 10-times revenues, to give you a 10-year payback, I have to pay you 100% of revenues for 10-straight years in dividends. That assumes I can get that by my shareholders. It also assumes I have zero cost of goods sold, which is very hard for a computer company.

That assumes zero expenses, which is hard with 39,000 employees. That assumes I pay no taxes, which is very hard. And that expects you pay no taxes on your dividends, which is kind of illegal. And that assumes with zero R&D for the next 10-years, I can maintain the current revenue run rate.

Now, having done that, would any of you like to buy my stock at $64? Do you realize how ridiculous those underlying assumptions are? You don’t need any transparency. You don’t need any footnotes.

What were you thinking?”

Many of the most popular “growth” stocks fit this insanity.

US Federal Deficit

The 2020 federal deficit is rapidly approaching $3 trillion after the biggest monthly increase on record in June.

This chart shows federal receipts and outlays over time.

US Economy

The streak of upside economic surprises continues. The June industrial production figures topped economists’ forecasts, as factory output climbed further.

- Capacity utilization bounced from extreme lows.

- Manufacturing production bounces higher.

- Despite improvements, many manufacturing sub-sectors are still in contraction territory.

- Retail sales rose sharply in June, exceeding expectations.

- Demand for automobiles has recovered.

- Mortgage rates hit another record low

US mortgage delinquencies are soaring. The chart below doesn’t include mortgages that are in forbearance.

Corporate defaults climbed sharply last quarter.

US bankruptcies continue to climb.

Here are the states with the highest and lowest percentage of past-due mortgages.

If the economy can’t recover unless consumer spending does, this next chart is problematic. It shows the average consumer credit and debit card spending, indexed to January of this year. As expected, we see a big drop coincident with the mid-March stay-at-home orders, followed by a slow recovery beginning in April. At the low point, spending was down almost 67% from January. By July 1, it was down “only” 33.8%.

There are two problems here. One is that after three months, only about half the lost spending has returned. Some of it is lost forever, too. An unsold hotel room is a permanently missed opportunity. More ominously, spending began pulling back in late June, about the time COVID-19 cases began rising in some states. Now, with restrictions returning, it seems likely to fall again. When consumer spending will get back to January’s level is anyone’s guess, but it doesn’t look like soon.

Copper’s downtrend resistance is holding.

The Great Acceleration

The future isn’t just happening, it’s happening faster. Washington policy expert Bruce Mehlman’s latest slide deck shows how technology, globalization, culture and politics are all combining to make 2020 a year like no other in US history.

Key Points:

- The US faces four concurrent “Super-Disrupters” this year: Recession, Pandemic, Mass Protests and an Intense Election.

- No single year since 1900 had all four of these. Only three other years had three of them (1919, 1957 and 1968).

- Foreseeable failures in pandemic preparation, economic policy and social justice sowed the seeds for this year’s crises.

- Culture wars have become business battles while both parties flee the political center and move toward the extremes.

- Meanwhile, digital disintermediation is accelerating as the internet cuts out middlemen in education, healthcare, retail and government.

- People are eager to vote in 2020 but also afraid of COVID, fraud and voter suppression. Both sides see turnout opportunities and risks.

Bottom Line: Crises have historically catalyzed reforms but they may not happen soon enough. Meanwhile the pandemic seems unlikely to wait. Other risks remain, too; Mehlman mentions cyberattacks, infrastructure failures and extreme weather events. His advice to corporate leaders: Trust is the most important brand attribute because you will be judged on how help in 2020. That sounds like good advice for individuals, too.

World Economy

Worldwide Q2 2020 Review

Expect extended low inflation/deflation, concurrent with high unemployment and sub-par growth.

Key Points:

A record 92.9% of national economies are now in recession. In 14 prior global recessions since 1871, the average was 54.3%. This slowdown’s synchronicity is unprecedented.

- World trade volume Is on track to fall 15% in 2020, with almost no prospect any country can counter the decline via expanded trade relationships.

- Record debt levels will depress growth unless offset by technology, demographics or new natural resources, none of which are in sight.

- Weaker debt productivity will put further downward pressure on the velocity of money.

- Record-setting corporate debt levels will prevent capital spending from growing as much as needed to generate new growth.

- Federal Reserve and other central bank programs are misallocating credit, sustaining failed businesses and preventing new firms from contributing to economic growth.

Bottom Line: A substantial deflationary gap has opened between potential and real GDP. Closing it will be difficult and time-consuming, which means persistent downward pressure on inflation and declining bond yields.

Four economic considerations suggest that years will pass before the economy returns to its prior cyclical 2019 peak performance. These four influences on future economic growth will mean that an extended period of low inflation or deflation will be concurrent with high unemployment rates and sub-par economic performance.

First, with over 90% of the world’s economies contracting, the present global recession has no precedent in terms of synchronization.

Therefore, no region or country is available to support or offset contracting economies, nor lead a powerful sustained expansion.

Second, a major slump in world trade volume is taking place. This means that one of the historical contributions to advancing global economic performance will be in the highly atypical position of detracting from economic advance as continued disagreements arise over trade barriers and competitive advantages.

Third, additional debt incurred by all countries, and many private entities, to mitigate the worst consequences of the pandemic, while humane, politically popular and in many cases essential, has moved debt to GDP ratios to uncharted territory. This ensures that a persistent misallocation of resources will be reinforced, constraining growth as productive resources needed for sustained growth will be unavailable.

Fourth, 2020 global per capita GDP is in the process of registering one of the largest yearly declines in the last century and a half and the largest decline since 1945. The lasting destruction of wealth and income will take time to repair.

Is Bankruptcy for Large Business a Good Thing?

Now we are trying to save those large companies. Some deserve it, I’m sure. But which ones and how many? You may remember Global Crossing. In the 1990s investment mania, it spent billions of dollars on undersea data cables, connecting the world. The data didn’t materialize fast enough, and Global Crossing went bankrupt. The new owners used the now-cheap assets to sell lower-cost connectivity. Huge losses for those investors, for which we should all be grateful, helped fund the era of cheap international communications.

The same happened with railroads in the 1870s. There was a mania by states and local governments to fund railroads connecting their cities and states. Every one of them went bankrupt, with the exception of one privately funded company (another story for another day about government programs). The bankrupt railroads with new owners offered cheaper travel which opened up the West.

The point is, keeping companies from going bankrupt is not always best for consumers and the economy. Now we are in different times. This is a crisis of unbelievably different and epic proportions. But the current “mania” to save all large businesses because they represent jobs should not become a habit. Fighting Mother Nature—or creative destruction—is not a good practice.

I want to end with a suggestion. Especially if you are retired, think about small, independent businesses where you spend money. Maybe a favorite bar or restaurant, a retail store, barber shop, or anything else. The owner is probably having a rough time right now. Find a chance to speak privately and see if you can help. Maybe you have capital, expertise, or other resources the business owner can use. Just offer whatever help you can, on whatever terms make sense for you.

Small business owners have their hands full even in normal times. Right now, they need all the help they can get. And we will all win by helping them pull through.

The Fed

In March, the Federal Reserve System came to the country’s rescue, announcing they would buy mortgage-backed securities, investment-grade corporate bonds, and even junk bond exchange-traded funds (ETFs). The Fed created a $750 billion “Corporate Credit Facilities” kitty to be used to stabilize the markets. Considering there is roughly $6

trillion in corporate bonds and another $1 trillion in high-yield bonds, that’s a big number. What’s notable is that the Fed has used just $42 billion of that $750 billion, and just $10.7 billion of that was used to buy corporate bonds. There is a lot more firepower to be spent, however that cash kitty is due to expire on September 30, 2020. But it won’t expire.

The Fed has embraced a “whatever it takes” mentality, and I suspect the facility will be extended. And there is more… at the last Federal Open Market Committee meeting, the Fed said they would buy between $250 and $500 million in commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS). These are fixed-income investment products that are backed by mortgages on commercial properties, as opposed to residential real estate. Large retail bankruptcies abound. Landlords are in trouble. No, it won’t expire on September 30, 2020.

The Fed’s balance sheet expansion has been THE reason for markets to explode to the upside. Over the last couple of months, the slowing rate of advance for the market has coincided with a reduction in the Fed’s “emergency measures.”

The limit to the Fed’s QE program is the government’s treasury issuance. An improving economy increased tax revenues, and improved outlooks began limiting the Fed’s ability to engage in more extensive monetary interventions.

Jerome Powell noted the Fed has to be careful not to “run through the corporate bond market.” The Fed is aware if they absorb too much of the treasury or corporate credit markets, they will distort pricing and create a negative incentive to lend. Such impairment would run counter to the very outcome they are trying to achieve.

As noted last week, there is already a “diminishing rate of return” on QE programs.

Instead, as each year passed, more monetary policy was required just to sustain economic growth. Whenever the Fed tightened policy, economic growth weakened, and financial markets declined. The table shows it takes increasingly larger amounts of QE to create an equivalent increase in asset prices.

Banks

Loan loss provisions at the largest US banks spiked in the second quarter.

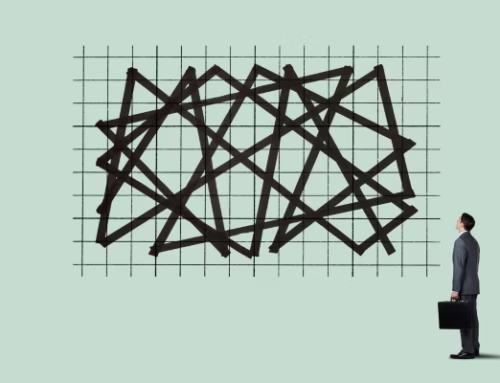

Hope

The current advance is not built on improving economic or fundamental data. It is largely built on “hope” that:

- The economy will improve in the second half of the year.

- Earnings will improve in the second half of the year.

- Oil prices will trade higher even as supply remains elevated.

- The Fed will not raise interest rates this year.

- Global Central Banks will “keep on keepin’ on.”

- The U.S. Dollar doesn’t rise

- Interest rates remain low.

- Bankruptcies and Delinquencies will subside.

- More stimulus will come from the Federal Government

- A vaccine will soon be available.

- The pandemic will subside

- There will be a “V-shaped” economic recovery

- Employment will recover quickly.

Market Data

- Last week, the smallest of options traders once again went on a speculative buying binge. Their net speculative activity is the most extreme since 2007, and when premiums are considered, it is by far the most extreme ever. All options traders spent 50% more on bullish strategies than bearish ones, among the highest amounts ever.

- The Nasdaq 100, which has helped to embolden traders with a historic winning streak, rallied more than 2% intraday to set a record high, then reversed enough to close down by more than 1%. The only other day in its history to do that was March 7, 2000. If we look at “only” 1% intraday rallies that reversed, then there were 10 days. Of those, 8 of them saw a negative return either 2 or 3 months later. The dates were 1996-12-12, 1997-01-23, 1998-06-25, 1998-07-21, 1998-12-03, 1999-04-07, 1999-04-27, 2000-01-24, 2000-02-25, and 2000-03-07.

- Even as the Nasdaq 100 (and broader Nasdaq) rallied to record highs, options traders have been pricing in higher volatility going forward, so there has been a positive correlation between the NDX and VXN. Breadth momentum has slowed, too, so the McClellan Oscillator was negative. Combined with Monday’s price reversal, it suggests caution.

- The history of market pullbacks since the Financial Crisis.

The S&P 500 return attribution by sector over the past five years.

Tech fund inflows have been unprecedented.

All content is the opinion of Brian J. Decker