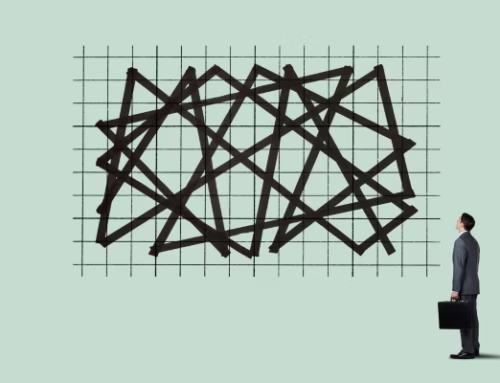

The Philadelphia Fed does a quarterly survey asking “professional forecasters” the probability of a recession in the next four quarters. It has a mixed track record, but is now almost twice what it was prior to the Great Recession. Professional forecasters tilt to the bullish side of the optimism street. When 43% of them think a recession likely within the next year, we should pay attention, especially after Mohamed’s warning this is not likely to be a typical business cycle recession.

Source: Bianco Research

Data maven Brent Donnelly notes:

Chicago PMI below 40 has called 8 of the last 8 recessions with zero misses. I will dig into whether or not it has clearer timing than 3m/10y (which has the same perfect track record but frustrating lags)

Source: Brent Donnelly

Peter Boockvar weighs in:

“A very important stat [is] the US personal savings rate which is now down to just 2.3%. The last time I saw something less was 2.1% in July 2005 in data going back to 1959.

“The bottom line is easy but unfortunate here, the savings well is running dry and why credit card usage, as mentioned by a few retailers over the past few weeks, is picking up. And this gets to my whole repeated point that it is almost impossible to avoid a recession when the cost of credit goes higher. Just as we need food to live, the US economy for the past 20+ years has needed cheap capital to grow and without a large pool of savings, that was ever more so. Now that savings is depleting and interest rates go higher, how do we not have a recession?”

Source: FRED

Again, Brent finds the odd bits of data that intrigue me and help set up an important point about Friday’s jobs report. He notes that there are two main ways people get paid in the US: hourly workers typically get paid once a week, and then salaried workers who get paid on the 15th and the last day of the month. The payrolls survey week contains the 12th so if the 12th is a Friday or Saturday, those salaried workers have not been paid yet. So, the hours worked/pay is lower for that reporting period. Strangely, the BLS does not adjust for that statistical quirk in their system. But it makes for some pretty bad misses.

Source: Brent Donnelly

US Economy

- Labor force participation declined again (including prime-age workers), which could contribute to faster wage growth. This is not the trend the Fed wants to see.

- Older Americans are not returning to work.

- The labor market “shortfall” is about 3.5 million.

- Casinos, hotels, restaurants, and bars continue to hire.

Source: @WSJ Read full article

- Industries with higher wages and more operating leverage are shedding workers quickly.

Source: PGM Global

- Here are the hiring “leaders and laggards.”

- The ISM index was well above expectations.

Source: Mizuho Securities USA

- Business activity accelerated.

- Business investment is expected to slow sharply.

A New Economy

I want to draw your attention to a very important thought piece in Foreign Affairs by Mohamed El-Erian, whom you may have known as head of PIMCO. Mohamed isn’t one to exaggerate and he’s certainly no “permabear.” So when he says to expect “Not Just Another Recession,” as he titled the article, I pay attention. You should, too.

Below are some excerpts, with my emphasis added in bold.

“To say that the last few years have been economically turbulent would be a colossal understatement. Inflation has surged to its highest level in decades, and a combination of geopolitical tensions, supply chain disruptions, and rising interest rates now threatens to plunge the global economy into recession. Yet for the most part, economists and financial analysts have treated these developments as outgrowths of the normal business cycle. From the US Federal Reserve’s initial misjudgment that inflation would be “transitory” to the current consensus that a probable US recession will be “short and shallow,” there has been a strong tendency to see economic challenges as both temporary and quickly reversible.

“But rather than one more turn of the economic wheel, the world may be experiencing major structural and secular changes that will outlast the current business cycle. Three new trends in particular hint at such a transformation and are likely to play an important role in shaping economic outcomes over the next few years: the shift from insufficient demand to insufficient supply as a major multi-year drag on growth, the end of boundless liquidity from central banks, and the increasing fragility of financial markets.

“These shifts help explain many of the unusual economic developments of the last few years, and they are likely to drive even more uncertainty in the future as shocks grow more frequent and more violent. These changes will affect individuals, companies, and governments—economically, socially, and politically. And until analysts wake up to the probability that these trends will outlast the next business cycle, the economic hardship they cause is likely to significantly outweigh the opportunities they create.”

Mohamed knows how to drive home his main point. This isn’t just the normal business cycle. We are experiencing something entirely different.

He goes on to talk about the COVID-related supply disruptions, but he thinks more is happening.

“As time passed, however, it became clear that the supply constraints stemmed from more than just the pandemic. Certain segments of the population exited the labor force at unusually high rates, either by choice or necessity, making it harder for companies to find workers. This problem was compounded by disruptions in global labor flows as fewer foreign workers received visas or were willing to migrate. Faced with these and other constraints, companies began to prioritize making their operations more resilient, not just more efficient.

“Meanwhile, governments intensified their weaponization of trade, investment, and payment sanctions—a response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and worsening tensions between the United States and China. Such changes accelerated the post-pandemic rewiring of global supply chains to aim for more ‘friend shoring’ and ‘near shoring.’”

This resiliency corporations now seek is a good idea, but it’s not the way most have operated for a very long time. And that switch to resiliency will take time and money

Mohamed next describes the Federal Reserve’s mistake.

“But the longer central banks extended what was meant to be a time-limited intervention—buying bonds for cash and keeping interest rates artificially low—the more collateral damage they caused. Liquidity-charged financial markets decoupled from the real economy, which reaped only limited benefits from these policies. The rich, who own the vast majority of assets, became richer, and markets became conditioned to think of central banks as their best friends, always there to curtail market volatility. Eventually, markets started to react negatively to even hints of a reduction in central bank support, effectively holding central banks hostage and preventing them from ensuring the health of the economy as a whole.

“All this changed with the surge in inflation that began in the first half of 2021. Initially misdiagnosing the problem as transitory, the Fed made the mistake of enabling mainly energy and food price hikes to explode into a broad-based cost-of-living phenomenon. Despite mounting evidence that inflation would not go away on its own, the Fed continued to pump liquidity into the economy until March 2022, when it finally began raising interest rates—and only modestly at first.

“But by then inflation had surged above seven percent and the Fed had backed itself into a corner… Instead of facing their normal dilemma—how to reduce inflation without harming economic growth and employment—the Fed now faces a trilemma: how to reduce inflation, protect growth and jobs, and ensure financial stability. There is no easy way to do all three, especially with inflation so high.

No one should be confident the Fed can juggle those three balls without dropping at least one.

Finally, Mohamed zeroes in on something we don’t discuss enough. Businesses, like consumers, respond to incentives. And the incentives have changed.

“These major structural changes go a long way toward explaining why growth is slowing in most of the world, inflation remains high, financial markets are unstable, and a surging dollar and interest rates have caused headaches in so many countries. Unfortunately, these changes also mean that global economic and financial outcomes are becoming harder to predict with a high degree of confidence. Instead of planning for one likely outcome—a baseline—companies and governments now have to plan for many possible outcomes. And some of these outcomes are likely to have a cascading effect, so that one bad event has a high probability of being followed by another. In such a world, good decision-making is difficult and mistakes are easily made.”

The leaders of large technology, financial, and energy firms operating internationally make giant bets assuming some baseline stability. Can they still do that? It’s tough. They saw COVID and now they’re dealing with inflation, war, and economic sanctions. All the incentives tell them to prioritize resiliency ahead of efficiency.

The efficiency they will have to sacrifice is what gave us those decades of low inflation. And unless something happens to restore it, we aren’t likely to see those conditions again.

Three Paradigm Shifts

If, as seems clear, we are in a new kind of economy now, it’s important to know the new landscape. The broad outlines are starting to show themselves.

The graphic below comes from a report by RSM Chief Economist Joseph Brusuelas, The post-pandemic era and the end of hyper-globalization. I like how it helps clarify the situation we now face, though of course it doesn’t capture every nuance.

Source: RSM

Looking at the 25 years or so ahead of the pandemic, the economy was characterized by

- Hyper-globalization as Western companies aggressively moved manufacturing overseas,

- Slow GDP growth, which got slower still as public and private debt burdens grew, and

- Abundant liquidity as central banks tried to stimulate growth via low rates and quantitative easing.

These weren’t going to last indefinitely in any case, but events since 2020 combined to reverse all three at the same time. So now we have three new paradigms.

- Shorter, more reliable supply chains,

- Even slower GDP growth, and

- Tighter credit amid higher inflation.

All this is easy to describe in a few paragraphs. Yet the real-life implications will probably be far greater than we can imagine. Add in the demographic shift as the population grows older and birth rates fall, and technological changes as artificial intelligence systems improve, plus possible lifestyle changes as we all adapt to scarce energy resources.

Then throw in massive global debt and what will become a sovereign debt problem as rates start biting into national budgets and it is a witch’s brew from Macbeth, bringing to mind that classic line: “Something wicked this way comes.” But wicked seems to be coming faster these days.

It’s not enough to say the times are a-changin’. The pace of change is accelerating, too. Change is coming faster and faster.

The Fed

Last week, many investors got excited when they thought Jerome Powell was turning dovish. This was a misreading of a Powell speech. But it still produced a market rally, which further data then reversed.

That was partly wishful thinking. Federal Reserve policy has been the bull’s best friend for 40 years now.

I don’t think Powell will “blink” again. If stopping inflation means starting a recession, he will choose recession. Note, however, this “recession” may not look like past ones.

I suspect we are going to need a new vocabulary to describe the 2020s economy and beyond. It has been, and will remain, unlike anything we have ever known or seen. Slower growth (I think an average of 1% for the decade), relatively low unemployment (over the cycle), and volatility will be the themes. Lots of investment opportunities but not buy-and-hold broad market indexes. This will be a decade for active management.

Further, the Federal Reserve is (finally!) moving to eliminate QE and theoretically will raise rates after that. I don’t want to get complicated here, but these two actions combined will further slow the velocity of money. Combined with the massive US debt, it is a recipe for economic slowdown.

If Powell doesn’t kill inflation, he will go down as possibly the worst Fed chair in history, which is saying something. I think he’s made of sterner stuff. He doesn’t need the money being an ex-Fed chair. He is thankfully not an East Coast-trained economist. He is a businessman who recognizes the insidious nature of inflation.

The FOMC won’t go straight from four consecutive 75-point rate hikes (in addition to two hikes of 25 and 50 basis points before those four) plus the anticipated 50-point hike next week to rate cuts in the first quarter or even the second. They will start by slowing the pace, then holding steady for at least a few months to see what happens. I’m confident the policy rate will remain where it is and maybe higher until mid-2023 at the soonest. Then when they do make cuts, we are not going back to the zero bound.

The possibilities form a kind of color spectrum.

Soft Landing: Demand slows, inflation falls to 3% range, unemployment doesn’t budge, GDP growth stays mildly positive.

Mild Slowdown: Inflation still falls, but at a much slower pace. Unemployment rises above 4%, GDP holds near 0% or slightly below.

“Normal” Recession: Inflation remains high and forces the Fed to keep hiking to 5% or more. Unemployment and GDP growth would get significantly worse.

Severe Recession: Other events send inflation higher than we have seen thus far. The Fed clamps down hard, unemployment surges, and GDP sinks to -3% or more for the full year.

Hard Landing: This would be a 1970s rerun, with double-digit inflation making the Fed raise rates to 10% or more, generating widespread business closures and mass unemployment.

Since commencing with the first interest-rate hike of 25 basis points in March, the Fed has increased the federal-funds target from a range of 0% to 0.25% to the current level of 3.75% to 4%. And based on recent comments from Powell, another increase of 50 basis points is all but certain at the monetary-policy meeting on December 13 and 14.

That means the Fed will have raised interest rates by 4.50% this year, far outpacing any of the other major global central banks. Take a look at the monetary-policy paths this year for our central bank compared with the Bank of England (“BOE”), European Central Bank (“ECB”), and the Reserve Bank of Australia (“RBA”)…

Since 1980, this has been the fastest tightening cycle by the Fed. But as we said earlier, those changes come at a cost. It’s more expensive to borrow money. In other words, there will be less money floating around in the financial system to spend.

But now, you have to return 6% to get back to flat. That’s a big change. And considering the S&P 500 is down 16.3% this year on a total return basis (dividends reinvested), that makes it very difficult for investors to get a REAL return, above inflation. Are you going to price a stock’s fair-value price-to-earnings (P/E) multiple at 17 or even 20 times like you did when interest rates were zero? Of course not.

Demand for labor remains extreme, suggesting that the Fed may need to tighten policy more than expected.

Housing Market

The Fed’s main power is its control of interest rates and liquidity. This power has limits, but it can seriously affect highly leveraged segments like housing. Let’s look at what is happening there because it’s not quite what you may think.

Between higher inflation expectations and the Fed’s exit from buying mortgage-backed securities, home mortgage rates are up significantly this year—enough to let a little air out of the housing bubble. Prices have dropped in many areas, making builders scale back their plans. But it’s not a “crash” yet.

Redfin, for example, expects the median US home price to drop about 4% in 2023 to $368,000. If it happens, that will be the first annual drop since 2012.

Source: Redfin

Looking at the year-over-year change, as in the chart above, makes this seem like a major change. But does it matter? Redfin’s own data shows the median home price was $293,000 in February 2020, just before COVID. So even with this drop, the median home will still be 26% more expensive than it was four years ago. And 30-year fixed mortgage rates have roughly doubled in that same time.

Here’s a longer-term look. This is HUD data so the numbers are a little different, but the trend is similar.

Source: FRED

The median home price almost tripled in the last 22 years, far outpacing inflation. Yes, all real estate is local, etc. Some areas are more or less expensive. But nationally speaking, this won’t be some kind of buyer’s paradise unless prices drop a lot more and mortgage rates retreat quite a bit.

That will push more people into rental housing, mainly apartments. I noted last week how rental prices softened in recent months. But here again, perspective is important. Demand is outpacing supply in many places, keeping rental rates higher than many people can afford. And that explains the headline: Millions of millennials moved in with their parents this year:

“Soaring rents forced millions of young Americans to move back in with their parents this year, according to a new survey.

“About one in four millennials are living with their parents, according to the survey of 1,200 people by Pollfish for the website PropertyManagement.com. That’s equivalent to about 18 million people between the ages of 26 and 41. More than half said they moved back in with family in the past year.

“Among the latter group, the surge in rental costs was the main reason given for the move. About 15 percent of millennial renters say that they’re spending more than half their after-tax income on rent.

“The disruptions of the pandemic, which triggered massive job losses as well as a spike in housing costs, have driven an unprecedented shakeup in living arrangements. In September of 2020, a survey by Pew found that for the first time since the Great Depression, a majority of Americans aged between 18 and 29 were living with their parents.

Source: Crain’s Detroit

We all know rents and home prices are coming down in real time but that inflation numbers don’t reflect that. Let’s unpack that.

The inflation benchmarks incorporate changes in housing prices gradually to reflect the fact they don’t affect most renters until lease renewal time. Basically, the methodology of the way they measure means that they stretch the data over a year.

Let’s do a thought experiment. Year one a widget costs $1. Twelve months later it costs $1.10, thus widget inflation is 10%. Add another 10% to make the next year’s price $1.21. Widget inflation is still only 10% for the past year, although over two years it was 21%.

Now, suppliers wake up and offer more widgets and the price stays the same for the next year. The inflation rate will show 0% inflation even though the price is still up 21% from three years ago.

Inflation as we measure and report it is an annualized affair. Home prices are now modestly dropping. That will show up in the inflation figures 12 months from now. In fact, home prices stopped rising (depending on where you live) this summer, so owner’s equivalent rent is slowly rolling over.

The housing market is like a roller coaster. As the cars go over the top of the track, there is a point where half the cars are falling and half the cars are still rising. That is roughly where we are on housing inflation. And like the roller coaster, the more cars roll over the top, the faster all the cars drop. But during that transition it still shows housing inflation as a lagging effect.

Barry Habib, who has won three out of the last 4 Zillow awards for most accurate housing and mortgage rate forecaster, says home mortgages will be 5% this summer. There is a great looming demand as household formation is getting ready to rise and there are not enough homes and apartments at affordable prices, thus young people living with parents. As Felix Zulauf says, the sun will come up and market prices will reset.

Put all that together and we can see that even in a sector where it has a great deal of influence, the Fed’s efforts thus far are only modestly reducing prices. That suggests rates will have to go quite a bit higher to have the desired effect.

Market Data

- The Dow’s outperformance vs. the S&P 500 hasn’t been this large since the 1930s.

- The S&P 500 is holding its downtrend resistance.

- The dollar tends to weaken at the end of the year.

Quote of the Week

“When we set out to do the best we can do, it is inevitable that great opportunity finds us because we are doing what truly makes us happy. We are in alignment and ready for the opportunities that life puts in our path.” – John Hinds

Picture of the Week

All content is the opinion of Brian J. Decker