Below we see the annualized rate of change (solid lines) and the cumulative change (dotted lines) in CPI and Core CPI since 2000. It appears that inflation is not a problem.

Let’s do some analysis of the Consumer Price Index, the best-known measure of inflation. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) divides all expenditures into eight categories and assigns a relative size to each. The pie chart below illustrates the components of the Consumer Price Index for Urban Consumers, the CPI-U, which we’ll refer to hereafter as the CPI.

What makes up the CORE CPI?

Now, let’s show the inflation (change of prices) for the many things we do in our lives that are NOT a part of the CORE statistic:

Federal Reserve and Economic Bailouts

There is a vast difference between today and 2009 when the Fed first launched QE-1 namely trailing valuations were 13x versus 30x currently. Also, pretty much every other metric is reversed as well.

If the market fell into a recession tomorrow, the Fed would be starting with roughly a $4 Trillion balance sheet with interest rates 2% lower than they were in 2009. In other words, the ability of the Fed to ‘bailout’ the markets today, is much more limited than it was in 2008.

Good News for the Market

- The November Markit PMI report showed further improvement in US factory activity.

- There was also an uptick in Markit’s services PMI.

- The Conference Board’s consumer confidence indicator ticked lower but remains elevated.

Bad News for the Market

- It’s shaping up to be a weak quarter for the Eurozone.

- Germany’s manufacturing sector remains deep in contraction territory.

- Car production has been depressed.

- The Chicago Fed National Activity Index remains in negative territory, pointing to soft fourth-quarter growth.

- Texas-area factory activity is deteriorating, pressured by the trade war and weakness in the energy sector. Factory orders have been slowing.

- Economists remain concerned about slowing business investment.

- Japan PMI indicators point to a GDP contraction this quarter.

- Australia’s consumer confidence tumbled to the lowest level since 2015 amid concerns about the economy.

- Mexico’s GDP growth has been soft.

* Foreign investment in the US is at multi-year lows.

The slump in China’s industrial profits has worsened.

Next, we have a couple of updates on Hong Kong.

Trade continues to deteriorate.

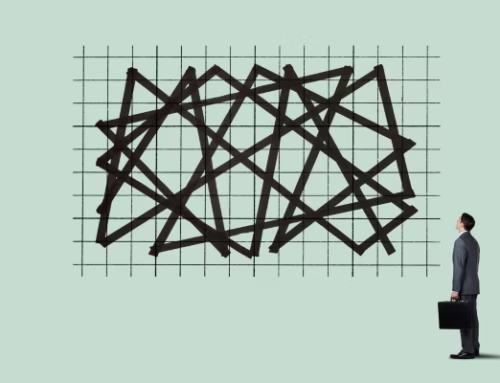

There is a widening gap between the S&P 500 and other indicators.

- S&P vs. the 10yr Treasury yield:

- S&P vs. high-yield bond spreads:

- S&P vs. investment-grade spreads:

- S&P vs. the rest of the world:

- S&P vs. copper:

Coal Production

Stock Buybacks

It is when a company buys back its own stock in the open market. A buyback reduces the number of outstanding shares available to investors. Buybacks can be great for investors when used appropriately – when a company’s shares are trading for cheap and it has enough extra cash to buy them.

Under the right conditions, Berkshire Hathaway CEO Warren Buffett believes they’re the best thing a company can do with its cash.

But not everyone feels the same way…

Democratic presidential candidate and Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders unveiled a plan last week to ban share buybacks altogether. He argued that they constitute stock-price manipulation and “provide absolutely no benefit to the job-creating productive economy.”

Are they good or bad?

The answer isn’t as simple… Share buybacks can be good, as Buffett believes. But as you’ll see, most companies don’t use them properly. Most companies tend to buy back tons of their own stocks near market tops. And they don’t do it at market bottoms, when they probably should be buying shares at a discount.

It’s a great time to talk about buybacks. We’re in never-before-seen territory. For the first time EVER, US share-buybacks topped $1T last year and we’re currently on track for more than $1 trillion in buybacks again this year.

Let’s use Macy’s as an extreme – yet informative – case study showing how share buybacks can become a disaster.

Every penny Macy’s has spent on share buybacks since 2000 has gone up in smoke. The expenditures didn’t benefit a single current shareholder.

For example, Macy’s spent a total of $5.8 billion on share buybacks in 2006 and 2007.

According to data compiled from market-research firm FactSet, the company’s stock peaked in March 2007 at $45.05 per share. It closed at a financial-crisis low of $7.42 in November 2008 – a drop of roughly 85%.

In other words, the company bought back nearly $6 billion in shares as its stock marched higher throughout 2006 and 2007.

Throughout 2008, with the stock trading at a price lower than any time since 1992, you might think Macy’s would’ve been salivating at the prospect of creating massive value through buybacks.

You would be wrong.

Macy’s suspended its share-buyback program in 2008 and didn’t restart it until 2011. After the company started buying back stock again, it kept buying back more and more shares as the price climbed higher.

The so-called “retail apocalypse” kicked into full gear in 2015. As a result, Macy’s stock price fell nearly in half that year – from more than $65 per share to less than $35 per share.

The market had clearly figured out that Macy’s was in trouble, but the company kept buying its shares back… It bought more than $7.6 billion worth of shares from 2011 until it again suspended the practice in early 2017. And as it became clear that online-retail juggernaut Amazon (AMZN) was permanently impairing the earnings power of mall-based retailers like Macy’s, the company’s stock fell into the $20s… then into the $10s.

From 2000 to the present, Macy’s board of directors has authorized a total of $18 billion in share buybacks. The company has used $16.3 billion for this purpose, leaving $1.7 billion unspent, as of its latest filings with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

Meanwhile, the company’s market cap peaked in July 2015 at around $23 billion. Today, it’s around $5 billion. That’s an $18 billion drop in market value over the past four years.

Coincidentally, it’s the exact amount the company’s board set aside for share buybacks over the past two decades.

It’s just a coincidence, but it provides a perfect example of how share buybacks can’t create lasting value for shareholders…

If a company’s business is declining and its share price is falling right along with it, share buybacks will only add to the damage done as the management team throws money away.

Maybe you’re thinking, “Macy’s had no idea the retail industry was in trouble when the company bought back its stock. It’s not their fault the stock tanked.”

That doesn’t sound right to me… If it isn’t the fault of management that the business destroyed $18 billion in shareholder value over the past two decades, then whose fault is it?

If Macy’s instead had paid all $16.3 billion out in cash dividends, the net benefit to long-term shareholders would have been a lot higher than what they got from the share buybacks.

Buybacks enrich corporate officers:

Over the past [three fiscal years], Electronic Arts bought back 22.8 million shares for $2.3 billion. Also, over the past [three fiscal years], Electronic Arts issued 10.7 million new shares to themselves for $211 million. About 1.5 million shares went to [Employee Stock Option Plan], and the rest to management.

Electronic Arts CEO Andrew Wilson exercised stock options and sold 30,000 shares of stock for more than $3 million in proceeds back in March… five days after announcing that the company would lay off 350 employees.

Microsoft spent $16.8 billion buying back 150 million shares in its most recent fiscal year, claiming it “returned capital to shareholders.” But the company also issued 116 million shares as employees exercised stock options and sold restricted stock units.

Roughly 70% of the nearly $17 billion in Microsoft’s buybacks went to managers who received options and restricted stock grants. Only 30% went to the company’s purported goal of returning capital to shareholders who actually bought the stock in the open market.

Technology giant Alphabet (GOOGL) bought back $11 billion and issued $10.4 billion in stock compensation, effectively negating all but $600 million of its multibillion-dollar buyback program. Social media pioneer Facebook (FB) bought back $9.5 billion but issued $4.5 billion in stock compensation. Those aren’t option exercises or restricted stock sales, but we all know they will be one day.

Trump and Powell

Like it or not, two men who work a few blocks apart in Washington DC arguably hold the global economy’s near-term future in their hands. Charles Gave thinks one of them is making a bad choice and the other is enabling it.

Key Points:

- President Trump clearly wants US interest rates to be much lower than they are, and even negative.

- The Fed’s policy rate should be somewhere around the “natural” rate, at which savings and investment are at equilibrium.

- Rates that are set too high encourage businesses to pay down debt instead of expand. Investment stalls and so does growth.

- Rates that are too low encourage investors to lever up and buy preexisting assets instead of building new ones. Stocks rise due to multiple expansion rather than earnings growth while lower investment makes productivity stall.

- After an initial boom, capital returns fall and borrowers can’t service their debts, leading to financial crisis as in 2008.

- Abnormally low interest rates are the cause of secular stagnation, not its cure.

- Trump’s tax cuts and deregulation policies helped raise capital returns. This was positive, but artificially lowering interest rates too far below the natural rate risks negating those benefits.

- By pressing Powell not to bring Fed rates closer to the natural rate, Trump risks triggering the next great financial crisis.

Bottom Line

Charles Gave thinks the Fed should keep short-term rates somewhere around 2% and is unworried about a stronger dollar. Trump insists rates should be lower. We may find out the hard way which of them is right.

Market Data

- The Intermediate Term Optimism Index’s 20-day average has risen to 78, one of the highest levels in years. The last time this happened was in April, just before stocks pulled back.